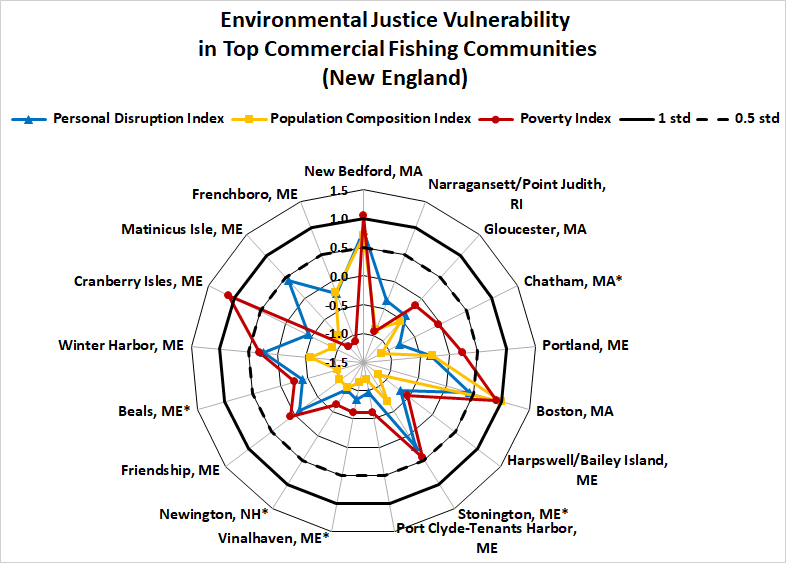

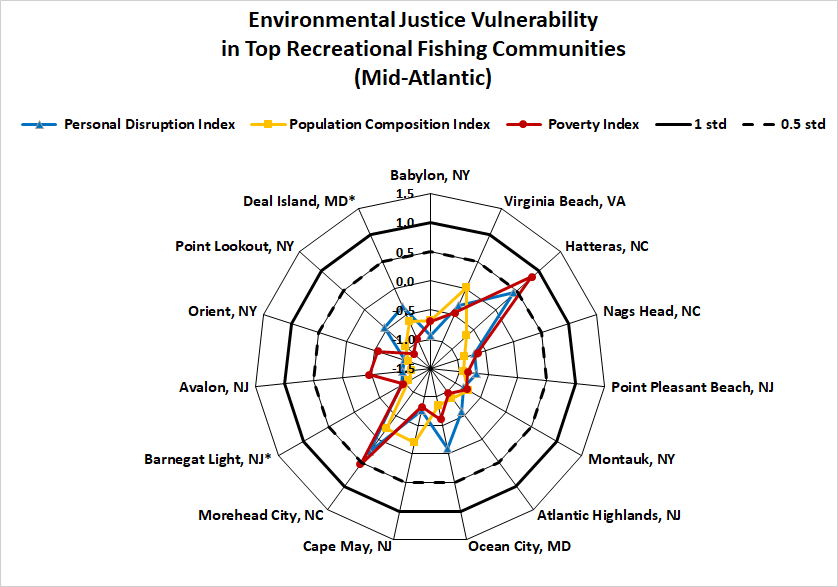

class: right, middle, my-title, title-slide .title[ # State of the Ecosystem Structure <br /> Proposed 2023 ] .subtitle[ ## SOE January Synthesis Meeting<br /> 18-19 January 2023 ] .author[ ### Sarah Gaichas, Kimberly Bastille, Geret DePiper, Kimberly Hyde, Scott Large, Sean Lucey, Laurel Smith<br /> Northeast Fisheries Science Center<br /> and all SOE contributors ] --- class: top, left <style> p.caption { font-size: 0.6em; } </style> <style> .reduced_opacity { opacity: 0.5; } </style> # State of the Ecosystem (SOE) reporting ## Improving ecosystem information and synthesis for fishery managers .pull-left[ - Ecosystem indicators linked to management objectives <a name=cite-depiper_operationalizing_2017></a>([DePiper, et al., 2017](https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/74/8/2076/3094701)) + Contextual information + Report evolving since 2016 + Fishery-relevant subset of full Ecosystem Status Reports - Open science emphasis <a name=cite-bastille_improving_2020></a>([Bastille, et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846155)) - Used within Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council's Ecosystem Process <a name=cite-muffley_there_2020></a>([Muffley, et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846156)) ] .pull-right[ *The IEA Loop<sup>1</sup>*  .footnote[ [1] https://www.integratedecosystemassessment.noaa.gov/national/IEA-approach ] ] ??? --- ## State of the Ecosystem: Maintain 2021-2022 structure for 2023 .pull-left[ ## 2023 Report Structure 1. Graphical summary + Page 1 report card re: objectives → + Page 2 risk summary bullets + Page 3 synthesis themes 1. Performance relative to management objectives 1. Risks to meeting management objectives ] .pull-right[ <table class="table" style="font-size: 14px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <caption style="font-size: initial !important;">Ecosystem-scale fishery management objectives</caption> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> Objective Categories </th> <th style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> Indicators reported </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr grouplength="6"><td colspan="2" style="border-bottom: 1px solid;"><strong>Provisioning and Cultural Services</strong></td></tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Seafood Production </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Landings; commercial total and by feeding guild; recreational harvest </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Profits </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Revenue decomposed to price and volume </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Recreation </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Angler trips; recreational fleet diversity </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Stability </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Diversity indices (fishery and ecosystem) </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Social & Cultural </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Community engagement/reliance and environmental justice status </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Protected Species </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Bycatch; population (adult and juvenile) numbers, mortalities </td> </tr> <tr grouplength="4"><td colspan="2" style="border-bottom: 1px solid;"><strong>Supporting and Regulating Services</strong></td></tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Biomass </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Biomass or abundance by feeding guild from surveys </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Productivity </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Condition and recruitment of managed species, primary productivity </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Trophic structure </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Relative biomass of feeding guilds, zooplankton </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Habitat </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Estuarine and offshore habitat conditions </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> ] --- ## State of the Ecosystem report structure: graphical summary (showing 2022) .pull-left[ .center[  ] ] .pull-right[ .center[  ] ] --- ## Ecosystem synthesis themes Characterizing ecosystem change for fishery management * Societal, biological, physical and chemical factors comprise the **multiple system drivers** that influence marine ecosystems through a variety of different pathways. * Changes in the multiple drivers can lead to **regime shifts** — large, abrupt and persistent changes in the structure and function of an ecosystem. * Regime shifts and changes in how the multiple system drivers interact can result in **ecosystem reorganization** as species and humans respond and adapt to the new environment. .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[  ] --- ## State of the Ecosystem report scale and figures .pull-left[ Spatial scale  A [glossary of terms](https://noaa-edab.github.io/tech-doc/glossary.html) (2021 Memo 5), detailed [technical methods documentation](https://NOAA-EDAB.github.io/tech-doc) and [indicator data](https://github.com/NOAA-EDAB/ecodata) are available online. ] .pull-right[ Key to figures <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-2-1.png" width="396" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Trends assessed only for 30+ years: [more information](https://noaa-edab.github.io/tech-doc/trend-analysis.html) <p style="color:#FF8C00;">Orange line = significant increase</p> <p style="color:#9932CC;">Purple line = significant decrease</p> No color line = not significant or < 30 years <p style="background-color:#D3D3D3;">Grey background = last 10 years</p> ] ] --- ## 2023 State of the Ecosystem Request tracking memo *SARAH STILL TO UPDATE* .scroll-output[ <table class="table" style="font-size: 12px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> Request </th> <th style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;"> Year </th> <th style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> Source </th> <th style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> Status </th> <th style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> Progress </th> <th style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> Memo Section </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Add "This report is for [audience]" </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In SOE </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Introduction section </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> State management objectives first in report </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In SOE </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Introduction section + Table </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 2 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Ocean acidification (OA) in NEFMC SOE </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In SOE </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Climate risks section </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 3 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Habitat impact of fishing based on gear. </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In SOE </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Habitat risks section </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 4 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Revisit right whale language </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In SOE </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Protected species section </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 5 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Sum of TAC/ Landings relative to TAC </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In SOE-MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Seafood production section </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 6 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Estuarine Water Quality </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In SOE-MAFMC, In progress-NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Climate and Habitat Risks sections MAFMC; Intern collated New England NERRS data </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 7 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> More direct opportunities for feedback </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> MAFMC SSC ecosystem subgroup </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 8 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Further definition of regime shift </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Regime shift analyses for specific indicators define "abrupt" and "persistent" quantitatively </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 9 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Expand collaboration with Canadian counterparts </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Currently drafting a NMFS-DFO climate/fisheries collaboration framework. </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 10 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Fall turnover date index </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> See Current Conditions report </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 11 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Links between species availability inshore/offshore (estuarine conditions) and trends in recreational fishing effort? </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Bluefish prey index inshore/offshore partially addresses </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 12 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Apex predator index (pinnipeds) </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Protected species branch developing time series </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 13 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Forage availability index (Herring/Sandlance) </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Bluefish prey index partially addresses </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 14 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Fishery gear modifications accounted for in shark CPUE? </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Updated methods in tech-doc </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 15 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Trend analysis </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Evaluating empirical thresholds </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 16 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Regime shifts in Social-Economic indicators </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> National working group and regional study </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 17 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Linking Condition </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Not ready for 2022 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 18 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Cumulative weather index </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Data gathered for prototype </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 19 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> VAST and uncertainty </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> Both Councils </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Not ready for 2022 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 20 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Seal index </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Not ready for 2022 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 21 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Breakpoints </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Evaluating empirical thresholds </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 22 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Management complexity </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2019 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Student work needs further analysis, no further work this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 23 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Shellfish growth/distribution linked to climate (system productivity) </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2019 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Project with A. Hollander </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 24 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Avg weight of diet components by feeding group </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2019 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> Internal </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Part of fish condition project </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 25 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Mean stomach weight across feeding guilds </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2019 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Intern evaluated trends in guild diets </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 26 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Inflection points for indicators </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2019 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> Both Councils </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> In progress </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Evaluating empirical thresholds </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 27 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Recreational bycatch mortality as an indicator of regulatory waste </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 28 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Sturgeon Bycatch </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 29 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Decomposition of diversity drivers highlighting social components </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 30 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Changing per capita seafood consumption as driver of revenue? </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 31 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Nutrient input, Benthic Flux and POC(particulate organic carbon ) to inform benthic productivity by something other than surface indidcators </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 32 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Relate OA to nutrient input; are there "dead zones" (hypoxia)? </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 33 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Indicators of chemical pollution in offshore waters </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 34 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> How does phyto size comp affect EOF indicator, if at all? </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> May pursue with MAFMC SSC eco WG </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 35 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Indicator of scallop pred pops poorly sampled by bottom trawls </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 36 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Compare EOF (Link) thresholds to empirical thresholds (Large, Tam) </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> May pursue with MAFMC SSC eco WG </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 37 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Time series analysis (Zooplankton/Forage fish) to tie into regime shifts </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC SSC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 38 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Optimum yield for ecosystem </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2021 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> May pursue with MAFMC SSC eco WG </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 39 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Re-evaluate EPUs </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 40 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Incorporate social sciences survey from council </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 41 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Biomass of spp not included in BTS </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 42 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Reduce indicator dimensionality with multivariate statistics </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2020 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> NEFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 43 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Estuarine condition relative to power plants and temp </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2019 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 44 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;width: 10.5cm; "> Young of Year index from multiple surveys </td> <td style="text-align:right;width: 1cm; "> 2019 </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 2cm; "> MAFMC </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 4.5cm; "> Not started </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 13.5cm; "> Lacking resources this year </td> <td style="text-align:left;width: 1.5cm; "> 45 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> ] --- ## Report structure revised in 2021 to address Council requests and improve synthesis .pull-left[ * Performance relative to management objectives - *What* does the indicator say--up, down, stable? - *Why* do we think it is changing: integrates synthesis themes - Multiple drivers - Regime shifts - Ecosystem reorganization * Objectives - Seafood production - Profits - Recreational opportunities - Stability - Social and cultural - Protected species ] .pull-right[ * Risks to meeting fishery management objectives - *What* does the indicator say--up, down, stable? - *Why* this is important to managers: integrates synthesis themes - Multiple drivers - Regime shifts - Ecosystem reorganization * Risk categories - Climate: warming, ocean currents, acidification - Habitat changes (incl. vulnerability analysis) - Productivity changes (system and fish) - Species interaction changes - Community structure changes - Other ocean uses - Offshore wind development ] --- background-image: url("https://github.com/NOAA-EDAB/presentations/raw/master/docs/EDAB_images//SOE-MA-final-03.23.22-no marks_Page_2.png") background-size: 500px background-position: right ## State of the Ecosystem Summary 2022: **Performance relative to management objectives** .pull-left-60[ Seafood production , status not evaluated Profits , status not evaluated Recreational opportunities: Effort  ; Effort diversity   Stability: Fishery  ; Ecological   Social and cultural, trend not evaluated, status of: * Fishing engagement and reliance by community * Environmental Justice (EJ) Vulnerability by community Protected species: * Maintain bycatch below thresholds   * Recover endangered populations (NARW)   ] .pull-right-40[] --- background-image: url("https://github.com/NOAA-EDAB/presentations/raw/master/docs/EDAB_images//SOE-MA-final-03.23.22-no marks_Page_3.png") background-size: 500px background-position: right ## State of the Ecosystem Summary 2022: **Risks to meeting fishery management objectives** .pull-left-60[ Climate: warming and changing oceanography continue * Heat waves and Gulf Stream instability * Estuarine, coastal, and offshore habitats affected, with range of species responses * Below average summer 2021 phytoplankton * Multiple fish with poor condition, declining productivity Other ocean uses: offshore wind development * Current revenue in proposed areas - 1-31% by port (some with EJ concerns) - 0-20% by managed species * Different development impacts for species preferring soft bottom vs. hard bottom * Overlap with one of the only known right whale foraging habitats, increased vessel strike and noise risks * Rapid buildout in patchwork of areas * Scientific survey mitigation required ] .pull-right-40[] --- # 2023 Performance relative to management objectives .center[      ] --- ## Objective: Mid Atlantic Seafood production     Risk elements: <span style="background-color:red;">ComFood</span> and <span style="background-color:orange;">RecFood</span>, unchanged .pull-left[ Indicator: Commercial landings <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-4-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Key: Black = Landings of all species combined; <p style="color:#FF6A6A;">Red = Landings of MAFMC managed species</p> ] ] .pull-right[ Indicators: Recreational harvest <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-5-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-6-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Multiple potential drivers of landings changes: ecosystem and stock production, management actions, market conditions (including COVID-19 disruptions), and environmental change. ??? The long-term declining trend in landings didn't change. --- ## Mid Atlantic Landings drivers: Stock status? TAC?   Risk elements: Fstatus, Bstatus, MgtControl .pull-left[ Indicator: Stock status <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-7-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Most stocks have good status. Butterfish B status has improved. Results from Dec 2022 Research Track assessments shown for Spiny dogfish (F above threshold) and bluefish (B above limit) do not represent official management advice. ] ] .pull-right[ Indicators: Total ABC or ACL, and Realized catch relative to management target <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-8-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-9-1.png" width="360" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Few managed species have binding limits; Management less likely playing a role ] ] ??? Stock status affects catch limits established by the Council, which in turn may affect landings trends. Summed across all MAFMC managed species, total Acceptable Biological Catch or Annual Catch Limits (ABC or ACL) have been relatively stable 2012-2020 (top). With the addition of blueline tilefish management in 2017, an additional ABC and ACL contribute to the total 2017-2020. Discounting blueline tilefish, the recent total ABC or ACL is lower relative to 2012-2013, with much of that decrease due to declining Atlantic mackerel ABC. Nevertheless, the percentage caught for each stock’s ABC/ACL suggests that these catch limits are not generally constraining as most species are well below the 1/1 ratio (bottom). Therefore, stock status and associated management constraints are unlikely to be driving decreased landings for the majority of species. --- ## Implications: Mid Atlantic Seafood Production Drivers .pull-left[ Biomass does not appear to drive landings trends <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-10-1.png" width="576" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Key: Black = NEFSC survey; <p style="color:#FF6A6A;">Red = NEAMAP survey</p> ] ] .pull-right[ .contrib[ * Declining managed benthos, aggregate planktivores <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-11-1.png" width="324" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> * Recreational drivers differ: shark fishery management, possibly survey methodology Monitor: * climate risks including warming, ocean acidification, and shifting distributions * ecosystem composition and production changes * fishing engagement ] ] ??? Because stock status is mostly acceptable, ABCs don't appear to be constraining for many stocks, and aggregate biomass trends appear stable, the decline in commercial landings is most likely driven by market dynamics affecting the landings of surfclams and ocean quahogs, as quotas are not binding for these species. Climate change also seems to be shifting the distribution of surfclams and ocean quahogs, resulting in areas with overlapping distributions and increased mixed landings. Given the regulations governing mixed landings, this could become problematic in the future and is currently being evaluated by the Council. --- ## Objective: New England Seafood production   .pull-left[ Indicators: Commercial landings <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-14-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Key: Black = Landings of all species combined; <p style="color:#FF6A6A;">Red = Landings of NEFMC managed species</p> ] ] .pull-right[ Indicators: Recreational harvest <br /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-15-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-16-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Multiple drivers: ecosystem and stock production, management, market conditions (including COVID-19 disruptions), and environmental change ??? Although scallop decreases are partially explained by a decreased TAC, analyses suggest that the drop in landings is at least partially due to market disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we do not anticipate the long-term declining trend in landings to change. --- ## New England Landings drivers: Stock status? Survey biomass? .pull-left[ Indicator: Stock status <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-17-1.png" width="540" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Stocks below BMSY increased from 8 to 9, stocks below ½ BMSY decreased from 6 to 4. Spiny dogfish results from RT are unofficial. Management still likely playing large role in seafood declines ] ] .pull-right[ Indicator: Survey biomass <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-18-1.png" width="576" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Biomass availability still seems unlikely driver ] ] --- ## New indicators for 2023: New England Realized catch compared to specified catch .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-19-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-20-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Implications: Discuss * Limited data for 2021 * Most species with catch > management target from Multispecies FMP --- ## Implications: New England Seafood Production .pull-left[ Drivers: * decline in commercial landings is most likely driven by the requirement to rebuild individual stocks as well as market dynamics * other drivers affecting recreational landings: shark fishery management, possibly survey methodology Monitor: * climate risks including warming, ocean acidification, and shifting distributions * ecosystem composition and production changes * fishing engagement <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-21-1.png" width="360" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-22-1.png" width="288" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /><img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-22-2.png" width="288" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Objective: Mid Atlantic Commercial Profits     Risk element: <span style="background-color:orange;">CommRev</span>, unchanged .pull-left[ Indicator: Commercial Revenue <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-24-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Key: Black = Revenue of all species combined; <p style="color:#FF6A6A;">Red = Revenue of MAFMC managed species</p> ] Recent change driven by benthos Monitor changes in climate and landings drivers: - Climate risk element: <span style="background-color:orange;">Surfclams</span> and <span style="background-color:red;">ocean quahogs</span> are sensitive to ocean warming and acidification. - pH in surfclam summer habitat is approaching, but not yet at, pH affecting surfclam growth ] .pull-right[ Indicator: Bennet--price and volume indices <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-25-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-26-1.png" width="540" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] ??? Recent declines in prices contributed to falling revenue as quantities landed did not increase enough to counteract declining prices. --- ## Objective: New England Commercial Profits  .pull-left[ Indicator: Commercial Revenue <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-28-1.png" width="540" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Key: Black = Revenue of all species combined; <p style="color:#FF6A6A;">Red = Revenue of NEFMC managed species</p> ] Both regions driven by single species * GOM high revenue despite low volume * Fluctuations in GB due to rotational management Monitor changes in climate and landings drivers: * Sea scallops and lobsters are sensitive to ocean warming and acidification ] .pull-right[ Indicator: Bennet--price and volume indices <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-29-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-30-1.png" width="540" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Objective: Mid Atlantic Recreational opportunities  ;   Risk element: <span style="background-color:yellow;">RecValue</span>, decreased risk; add diversity? .pull-left[ Indicators: Recreational effort and fleet diversity <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-32-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-33-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ Implications * Increased angler trips in 2020 relative to previous years strongly influenced the previously reported long term increase in recreational effort. Adding 2021 data, recreational effort (angler trips) has no long term trend. * The increasing long term trend from 2021 changed the risk categories for the RecValue element to low-moderate (previously ranked high risk). No trend indicates low risk. * Decline in recreational fleet diversity suggests a potentially reduced range of opportunities. * Driven by party/charter contraction and a shift toward shore based angling. ] ??? Changes in recreational fleet diversity can be considered when managers seek options to maintain recreational opportunities. Shore anglers will have access to different species than vessel-based anglers, and when the same species, typically smaller fish. Many states have developed shore-based regulations where the minimum size is lower than in other areas and sectors to maintain opportunities in the shore angling sector. --- ## Objective: New England Recreational opportunities   .pull-left[ Indicators: Recreational effort and fleet diversity <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-35-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-36-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ Implications * Absence of a long-term trend in recreational effort suggests relative stability in the overall number of recreational opportunities in New England ] --- ## Objective: Mid Atlantic Environmental Justice and Social Vulnerability   Risk element: <span style="background-color:yellow;">Social</span> Indicators: Environmental justice vulnerability, commercial fishery engagement and reliance .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-38-1.png" width="468" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Mid-Atlantic commercial fishing communities ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-39-1.png" width="100%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <!----> ] Implications: Highlighted communities may be vulnerable to changes in fishing patterns due to regulations and/or climate change. When also experiencing environmental justice issues, they may have lower ability to successfully respond to change. ??? These plots provide a snapshot of the presence of environmental justice issues in the most highly engaged and most highly reliant commercial and recreational fishing communities in the Mid-Atlantic. These communities may be vulnerable to changes in fishing patterns due to regulations and/or climate change. When any of these communities are also experiencing social vulnerability including environmental justice issues, they may have lower ability to successfully respond to change. --- ## Objective: Mid Atlantic Environmental Justice and Social Vulnerability   Risk element: <span style="background-color:yellow;">Social</span> Indicators: Environmental justice vulnerability, recreational fishery engagement and reliance .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-40-1.png" width="468" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Mid-Atlantic recreational fishing communities ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-41-1.png" width="100%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <!----> ] Implications: Highlighted communities may be vulnerable to changes in fishing patterns due to regulations and/or climate change. When also experiencing environmental justice issues, they may have lower ability to successfully respond to change. --- ## Objective: New England Environmental Justice and Social Vulnerability Indicators: Environmental justice vulnerability, commercial fishery engagement and reliance .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-43-1.png" width="468" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> New England commercial fishing communities ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-44-1.png" width="100%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <!----> ] Implications: Highlighted communities may be vulnerable to changes in fishing patterns due to regulations and/or climate change. When also experiencing environmental justice issues, they may have lower ability to successfully respond to change. ??? These plots provide a snapshot of the presence of environmental justice issues in the most highly engaged and most highly reliant commercial and recreational fishing communities in the Mid-Atlantic. These communities may be vulnerable to changes in fishing patterns due to regulations and/or climate change. When any of these communities are also experiencing social vulnerability including environmental justice issues, they may have lower ability to successfully respond to change. --- ## Objective: New England Environmental Justice and Social Vulnerability Indicators: Environmental justice vulnerability, recreational fishery engagement and reliance .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-45-1.png" width="468" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> New England recreational fishing communities ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-46-1.png" width="100%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <!----> ] Implications: Highlighted communities may be vulnerable to changes in fishing patterns due to regulations and/or climate change. When also experiencing environmental justice issues, they may have lower ability to successfully respond to change. --- ## Objective: Mid Atlantic Fishery Stability     Risk elements: <span style="background-color:lightgreen;">FishRes1</span> and <span style="background-color:lightgreen;">FleetDiv</span>, unchanged .pull-left[ *Fishery* Indicators: Commercial fleet count, fleet diversity <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-48-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Most recent fleet counts at low range of series ] ] .pull-right[ *Fishery* Indicators: commercial species revenue diversity, recreational species catch diversity <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-49-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Most recent near series low value. Covid role? ] <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-50-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Objective: Mid Atlantic Ecological Stability     Risk element: ecological diversity put aside, new indices .pull-left[ *Ecological* Indicators: zooplankton and larval fish diversity <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-51-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-52-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ *Ecological* Indicator: expected number of species, NEFSC bottom trawl survey <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-53-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Implications: * stable capacity to respond to the current range of commercial fishing opportunities * recreational catch diversity maintained by a different set of species over time * monitor zooplankton diversity driven by declining dominant species ] ??? While larval and adult fish diversity indices are stable, a few warm-southern larval species are becoming more dominant. Increasing zooplankton diversity is driven by declining dominance of an important species, which warrants continued monitoring. --- ## Objective: New England Fishery Stability  Com ; Rec  .pull-left[ *Fishery* Indicators: Commercial fleet count, fleet diversity <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-55-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Most recent around lowest points in series ] ] .pull-right[ *Fishery* Indicators: commerical species revenue diversity, recreational species catch diversity <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-56-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Most recent lowest point in series. Covid role? ] <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-57-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Objective: New England Ecological Stability   .pull-left[ *Ecological* Indicators: zooplankton and larval fish diversity <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-58-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-59-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ *Ecological* Indicator: expected number of species, NEFSC bottom trawl survey <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-60-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Implications: * Commercial fishery diversity driven by small number of species * Diminished capacity to respond to future fishing opportunities * Recreational diversity due to species distributions and regulations * Adult diversity in GOM suggests increase in warm-water species ] ??? * Overall stability in the fisheries and ecosystem components * Increasing diversity in several indicators warrants continued monitoring --- ## Objectives: All Areas Protected species *Maintain bycatch below thresholds*   .pull-left[ Indicators: Harbor porpoise and gray seal bycatch .reduced_opacity[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-61-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-62-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] ] .pull-right[ Implications: * Currently meeting objectives * Risk element: TechInteract, evaluated by species and sector: 14 <span style="background-color:lightgreen;">low</span>, 6 <span style="background-color:yellow;">low-mod</span>, 3 <span style="background-color:orange;">mod-high</span> risk, unchanged * The downward trend in harbor porpoise bycatch can also be due to a decrease in harbor porpoise abundance in US waters, reducing their overlap with fisheries, and a decrease in gillnet effort. * The increasing trend in gray seal bycatch may be related to an increase in the gray seal population (U.S. pup counts). ] --- ## Objectives: All Areas Protected species *Recover endangered populations*   .pull-left[ Indicators: North Atlantic right whale population, calf counts <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-63-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-64-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ Implications: * Population drivers for North Atlantic Right Whales (NARW) include combined fishery interactions/ship strikes, distribution shifts, and copepod availability. * Additional potential stressors include offshore wind development, which overlaps with important habitat areas used year-round by right whales, including mother and calf migration corridors and foraging habitat. * Unusual mortality events continue for 3 large whale species. <!--* Risk elements: - FW2Prey evaluated by species: 13 <span style="background-color:lightgreen;">low</span>, 3 <span style="background-color:yellow;">low-mod</span> risk, unchanged - TechInteract, evaluated by species and sector, unchanged--> ] --- # 2023 Risks to meeting fishery management objectives .center[   ] .center[      ] --- background-image: url("https://github.com/NOAA-EDAB/presentations/raw/master/docs/EDAB_images//seasonal-sst-anom-gridded-2022.png") background-size: 700px background-position: right top ## Risks: Climate change Mid Atlantic .pull-left[ Indicators: ocean currents, bottom and surface temperature, *detrended* marine heatwaves <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-66-1.png" width="288" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-67-1.png" width="288" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-68-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-69-1.png" width="360" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] ??? A marine heatwave is a warming event that lasts for five or more days with sea surface temperatures above the 90th percentile of the historical daily climatology (1982-2011). --- ## Risks: Climate change Mid Atlantic, new bottom temperature indicators .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-70-1.png" width="576" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ In contrast to SST, long term BT is increasing in winter as well as other seasons ] ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-71-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-72-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .contrib[ Heatwaves in bottom temperature last longer and happen later in the season than surface heatwaves. No consistent long term annual trend in bottom or surface heatwaves. ] ] --- ## Risks: Climate change Mid Atlantic, new seasonal transition indicators .pull-left[ Mid Atlantic <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-73-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-74-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ Coastwide <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-75-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-76-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- background-image: url("https://github.com/NOAA-EDAB/presentations/raw/master/docs/EDAB_images/seasonal-sst-anomaly-gridded-NE2022.png") background-size: 600px background-position: right ## Risks: Climate change New England .pull-left[ Indicators: ocean currents, bottom and surface temperature <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-78-1.png" width="288" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .reduced_opacity[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-79-1.png" width="288" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-80-1.png" width="432" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Risks: Climate change New England .pull-left[ Indicators: *detrended* marine heatwaves <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-81-1.png" width="360" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-82-1.png" width="360" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-83-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-84-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Risks: Climate change New England, new bottom temperature indicators .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-85-1.png" width="576" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-86-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-87-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Risks: Climate change New England, bottom heatwaves cont'd + new seasonal transition indicators .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-88-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-89-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-90-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-91-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Risks: Climate change and estuarine habitat   Risk element: EstHabitat 11 <span style="background-color:lightgreen;">low</span>, 4 <span style="background-color:red;">high</span> risk species .pull-left[ Indicators: Chesapeake Bay temperature and salinity <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-94-1.png" width="432" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-95-1.png" width="432" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ Indicator: SAV trends in Chesapeake Bay <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-96-1.png" width="432" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Indicator: Water quality attainment .reduced_opacity[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-97-1.png" width="432" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] ] --- ## Risks: Climate change and offshore habitat .pull-left[ Indicator: cold pool indices <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-98-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Indicator: Mid Atlantic Ocean acidification  ] .pull-right[ Indicator: warm core rings <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-99-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Indicator: New England Ocean acidification  ] --- ## Risks: Ecosystem productivity Mid Atlantic   Risk element: <span style="background-color:yellow;">EcoProd</span> Indicators: chlorophyll, primary production, zooplankton .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-100-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-101-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-102-1.png" width="576" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Implications: increased production by smaller phytoplankton implies less efficient transfer of primary production to higher trophic levels. Monitor implications of increasing gelatinous zooplankton and krill. ??? Below average phytoplankton biomass could be due to reduced nutrient flow to the surface and/or increased grazing pressure. A short fall bloom was detected in November. Primary productivity (the rate of photosynthesis) was average to below average throughout 2021 --- ## Risks: Ecosystem productivity Mid Atlantic   Risk element: <span style="background-color:yellow;">EcoProd</span> .pull-left[ Indicator: fish condition <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-103-1.png" width="120%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <!----> ] .pull-right[ Indicator: fish productivity anomaly <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-104-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Implications: Species in the MAB had mixed condition in 2022. Survey-based fish productivity continues a general decline. Update? *Preliminary results of synthetic analyses show that changes in temperature, zooplankton, fishing pressure, and population size influence the condition of different fish species.* ??? --- ## Risks: Ecosystem productivity New England Indicators: chlorophyll, primary production .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-106-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-107-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Implications: increased production by smaller phytoplankton implies less efficient transfer of primary production to higher trophic levels. Monitor implications of increasing gelatinous zooplankton and krill. ??? Below average phytoplankton biomass could be due to reduced nutrient flow to the surface and/or increased grazing pressure. A short fall bloom was detected in November. Primary productivity (the rate of photosynthesis) was average to below average throughout 2021 --- ## Risks: Ecosystem productivity New England Indicator: fish condition .pull-left[ Georges Bank <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-108-1.png" width="120%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ Gulf of Maine <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-109-1.png" width="120%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Implications: Many species in New England showed improved condition in 2021-2022. Preliminary results of synthetic analyses show that changes in temperature, zooplankton, fishing pressure, and population size influence the condition of different fish species. --- ## Risks: Ecosystem productivity New England Indicator: fish productivity anomaly .pull-left[ <div class="figure" style="text-align: center"> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/productivity-anomaly-gb-1.png" alt="Small fish per large fish biomass anomaly on Georges Bank. The summed anomaly across species is shown by the black line." width="504" /> <p class="caption">Small fish per large fish biomass anomaly on Georges Bank. The summed anomaly across species is shown by the black line.</p> </div> ] .pull-right[ <div class="figure" style="text-align: center"> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/productivity-anomaly-gom-1.png" alt="Small fish per large fish biomass anomaly in the Gulf of Maine. The summed anomaly across species is shown by the black line." width="504" /> <p class="caption">Small fish per large fish biomass anomaly in the Gulf of Maine. The summed anomaly across species is shown by the black line.</p> </div> ] Survey based fish productivity shows no clear trend in New England. --- ## Risks: Ecosystem productivity, new fish productivity anomaly based on stock assessments .pull-left[ Mid Atlantic region stocks <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-110-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ New England region stocks <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-111-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Methods from <a name=cite-perretti_regime_2017></a>([Perretti, et al., 2017](http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v574/p1-11/)). Black line indicates sum where there are the same number of assessments across years. --- ## Risks: Ecosystem productivity All regions <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-112-1.png" width="90%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Implications: fluctuating environmental conditions and prey for forage species affect both abundance and energy content. Energy content varies by season, and has changed over time most dramatically for Atlantic herring --- ## Risks: Ecosystem structure All regions Indicators: distribution shifts, diversity (previous sections) predator status and trends here .pull-left[ *No trend in aggregate sharks* <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-113-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> * No obvious increase in shark populations * Most highly migratory fish predators are not depleted: - 10 above B target - 7 above B limit but below B target - 2 below B limit ] .pull-right[ *HMS populations mainly at or above target* <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-114-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Risks: Ecosystem structure New England Indicators: predators .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-115-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ *Gray seals increasing* * Breeding season ~ 27,000 US gray seals, Canada's population ~ 425,000 (2016) * Canada's population increasing at ~ 4% per year * U.S. pupping sites increased from 1 (1988) to 9 (2019) * Harbor and gray seals are generalist predators that consume more than 30 different prey species: red, white and silver hake, sand lance, yellowtail flounder, four-spotted flounder, Gulf-stream flounder, haddock, herring, redfish, and squids. Implications: stable predator populations suggest stable predation pressure on managed species, but increasing predator populations may reflect increasing predation pressure. ] --- ## Risks: Ecosystem structure New England .pull-left-40[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-116-1.png" width="360" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Common tern productivity decline reflecting prey, other drivers? Discuss ] .pull-right-60[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-117-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-118-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Risks: Ecosystem structure: new diet based forage fish index .pull-left[ Mid Atlantic <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-120-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ New England <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-121-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Is the forage base changing over time? .contrib[ VAST model using 22 predators to sample 20 forage fish groups, includes more unmanaged forage (anchovies, sandlance) than direct survey trawl data. ] --- ## Risks: Habitat climate vulnerability   New, opportunity to refine habitat risks Indicators: climate sensitive species life stages mapped to climate vulnerable habitats *See MAFMC 2022 EAFM risk assessment for example species narratives* <div id="htmlwidget-eff6d17aacfaa8caa25e" style="width:100%;height:226.8px;" class="widgetframe html-widget"></div> <script type="application/json" data-for="htmlwidget-eff6d17aacfaa8caa25e">{"x":{"url":"20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html//widgets/widget_midHabTable.html","options":{"xdomain":"*","allowfullscreen":false,"lazyload":false}},"evals":[],"jsHooks":[]}</script> --- ## Risks: Habitat: new habitat diversity trend indicators .pull-left[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-122-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-123-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] Implications: discuss --- ## Implications: Climate change and managed species   Risk elements unchanged, new info: .pull-left[ Climate: 6 <span style="background-color:lightgreen;">low</span>, 3 <span style="background-color:yellow;">low-mod</span>, 4 <span style="background-color:orange;">mod-high</span>, 1 <span style="background-color:red;">high</span> risk *Multiple drivers with different impacts by species* * Seasonal estuarine conditions affect life stages of striped bass, blue crabs, summer flounder, black sea bass differently .contrib[ + Chesapeake summer hypoxia, temperature better than in past years, but worse in fall + Habitat improving in some areas (tidal fresh SAV, oyster reefs), but eelgrass declining ] * Ocean acidification impact on vulnerable surfclams .contrib[ + Areas of low pH identified in surfclam and scallop habitat + Lab work identified pH thresholds for surfclam growth ] * Warm core rings important to *Illex* availability. Fishing effort concentrates on the eastern edge of warm core rings, where upwelling and enhanced productivity ocurr ] .pull-right[ DistShift: 2 <span style="background-color:lightgreen;">low</span>, 9 <span style="background-color:orange;">mod-high</span>, 3 <span style="background-color:red;">high</span> risk species .contrib[ Shifting species distributions alter both species interactions, fishery interactions, and expected management outcomes from spatial allocations and bycatch measures based on historical fish and protected species distributions. ] *New Indicator: protected species shifts* <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-124-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] ] --- ## Risks: Offshore Wind Development Mid Atlantic   Element: OceanUse .pull-left[ Indicators: development timeline, fishery and community specific revenue in lease areas <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-125-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-126-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-127-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Risks: Offshore Wind Development New England .pull-left[ Indicators: fishery and community specific revenue in lease areas <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-129-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="20230119_SOEoverview_Gaichas_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-130-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- background-image: url("https://github.com/NOAA-EDAB/ecodata/raw/master/workshop/images/right_whales.jpg") background-size: 500px background-position: right ## Risks: Offshore Wind Development Summary .pull-left[ Implications: *revise* * X% of port revenue from fisheries currently comes from areas proposed for offshore wind development. Some communities have environmental justice concerns and gentrification vulnerability. * Up to Y% of annual commercial landings and revenue for Mid-Atlantic species occur in lease areas. * Development will affect species differently, negatively affecting species that prefer soft bottom habitat while potentially benefiting species that prefer hard structured habitat. * Planned wind areas overlap with one of the only known right whale foraging habitats, and altered local oceanography could affect right whale prey availability. Development also brings increased vessel strike risk and the potential impacts of pile driving noise. ] .pull-right[] ??? Current plans for rapid buildout of offshore wind in a patchwork of areas spreads the impacts differentially throughout the region Evaluating the impacts to scientific surveys has begun. --- background-image: url("https://github.com/NOAA-EDAB/presentations/raw/master/docs/EDAB_images//noaa-iea.png") background-size: 350px background-position: right bottom ## THANK YOU! SOEs made possible by (at least) 61 contributors from 14 institutions UPDATE THIS! .pull-left[ .contrib[ Kimberly Bastille<br> Aaron Beaver (Anchor QEA)<br> Andy Beet<br> Ruth Boettcher (Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries)<br> Mandy Bromilow (NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office)<br> Zhuomin Chen (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)<br> Joseph Caracappa<br> Doug Christel (GARFO)<br> Patricia Clay<br> Lisa Colburn<br> Jennifer Cudney (NMFS Atlantic HMS Management Division)<br> Tobey Curtis (NMFS Atlantic HMS Management Division)<br> Geret DePiper<br> Dan Dorfman (NOAA-NOS-NCCOS)<br> Hubert du Pontavice<br> Emily Farr (NMFS Office of Habitat Conservation)<br> Michael Fogarty<br> Paula Fratantoni<br> Kevin Friedland<br> Marjy Friedrichs (VIMS)<br> Sarah Gaichas<br> Ben Galuardi (GARFO)<br> Avijit Gangopadhyay (School for Marine Science and Technology, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth)<br> James Gartland (Virginia Institute of Marine Science)<br> Glen Gawarkiewicz (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)<br> Sean Hardison<br> Kimberly Hyde<br> John Kosik<br> Steve Kress (National Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program)<br> Young-Oh Kwon (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)<br> ] ] .pull-right[ .contrib[ Scott Large<br> Andrew Lipsky<br> Sean Lucey<br> Don Lyons (National Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program)<br> Chris Melrose<br> Shannon Meseck<br> Ryan Morse<br> Brandon Muffley (MAFMC)<br> Kimberly Murray<br> Chris Orphanides<br> Richard Pace<br> Tom Parham (Maryland DNR)<br> Charles Perretti<br> CJ Pellerin (NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office)<br> Grace Roskar (NMFS Office of Habitat Conservation)<br> Grace Saba (Rutgers)<br> Vincent Saba<br> Sarah Salois<br> Chris Schillaci (GARFO)<br> Dave Secor (CBL)<br> Angela Silva<br> Adrienne Silver (UMass/SMAST)<br> Emily Slesinger (Rutgers University)<br> Laurel Smith<br> Talya tenBrink (GARFO)<br> Bruce Vogt (NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office)<br> Ron Vogel (UMD Cooperative Institute for Satellite Earth System Studies and NOAA/NESDIS Center for Satellite Applications and Research)<br> John Walden<br> Harvey Walsh<br> Changhua Weng<br> Mark Wuenschel ] ] --- ## References .contrib[ <a name=bib-bastille_improving_2020></a>[Bastille, K. et al.](#cite-bastille_improving_2020) (2020). "Improving the IEA Approach Using Principles of Open Data Science". In: _Coastal Management_ 0.0. Publisher: Taylor & Francis \_ eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846155, pp. 1-18. ISSN: 0892-0753. DOI: [10.1080/08920753.2021.1846155](https://doi.org/10.1080%2F08920753.2021.1846155). URL: [https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846155](https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846155) (visited on Dec. 09, 2020). <a name=bib-depiper_operationalizing_2017></a>[DePiper, G. S. et al.](#cite-depiper_operationalizing_2017) (2017). "Operationalizing integrated ecosystem assessments within a multidisciplinary team: lessons learned from a worked example". En. In: _ICES Journal of Marine Science_ 74.8, pp. 2076-2086. ISSN: 1054-3139. DOI: [10.1093/icesjms/fsx038](https://doi.org/10.1093%2Ficesjms%2Ffsx038). URL: [https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/74/8/2076/3094701](https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/74/8/2076/3094701) (visited on Mar. 09, 2018). <a name=bib-muffley_there_2020></a>[Muffley, B. et al.](#cite-muffley_there_2020) (2020). "There Is no I in EAFM Adapting Integrated Ecosystem Assessment for Mid-Atlantic Fisheries Management". In: _Coastal Management_ 0.0. Publisher: Taylor & Francis \_ eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846156, pp. 1-17. ISSN: 0892-0753. DOI: [10.1080/08920753.2021.1846156](https://doi.org/10.1080%2F08920753.2021.1846156). URL: [https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846156](https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846156) (visited on Dec. 09, 2020). <a name=bib-perretti_regime_2017></a>[Perretti, C. et al.](#cite-perretti_regime_2017) (2017). "Regime shifts in fish recruitment on the Northeast US Continental Shelf". En. In: _Marine Ecology Progress Series_ 574, pp. 1-11. ISSN: 0171-8630, 1616-1599. DOI: [10.3354/meps12183](https://doi.org/10.3354%2Fmeps12183). URL: [http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v574/p1-11/](http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v574/p1-11/) (visited on Feb. 10, 2022). ] ## Additional resources .pull-left[ * [ecodata R package](https://github.com/noaa-edab/ecodata) * Visualizations: * [Mid-Atlantic Human Dimensions indicators](http://noaa-edab.github.io/ecodata/human_dimensions_MAB) * [Mid-Atlantic Macrofauna indicators](http://noaa-edab.github.io/ecodata/macrofauna_MAB) * [Mid-Atlantic Lower trophic level indicators](https://noaa-edab.github.io/ecodata/LTL_MAB) * [New England Human Dimensions indicators](http://noaa-edab.github.io/ecodata/human_dimensions_NE) * [New England Macrofauna indicators](http://noaa-edab.github.io/ecodata/macrofauna_NE) * [New England Lower trophic level indicators](https://noaa-edab.github.io/ecodata/LTL_NE) ] .pull-right[ * [SOE Reports on the web](https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/new-england-mid-atlantic/ecosystems/state-ecosystem-reports-northeast-us-shelf) * [SOE Technical Documentation](https://noaa-edab.github.io/tech-doc) * [Draft indicator catalog](https://noaa-edab.github.io/catalog/) .contrib[ * Slides available at https://noaa-edab.github.io/presentations * Contact: <Sarah.Gaichas@noaa.gov> ] ]